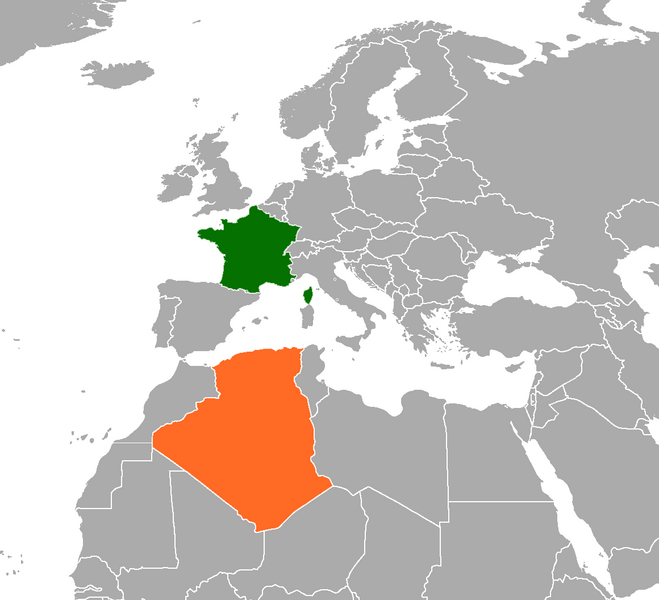

France is reconsidering a long-standing migration agreement with Algeria, further escalating tensions between the two nations. French Prime Minister François Bayrou announced on

Wednesday that his government would review the 1968 migration pact, which has historically facilitated Algerian settlement in France. This decision comes amid a broader crackdown on immigration, led by Interior Minister Bruno Retailleau, who has accused Algiers of deliberately obstructing deportations.

A diplomatic rift deepens

Bayrou’s announcement marks a significant shift in Franco-Algerian relations, as Paris prepares to reassess multiple immigration agreements dating back to Algeria’s independence in 1962. In addition to revisiting these treaties, France intends to present Algeria with a list of nationals it seeks to deport.

The already strained relationship took a severe hit last week following a violent attack in Mulhouse, where an undocumented Algerian national, reportedly suffering from schizophrenia, killed one person and injured six others in a stabbing incident. Retailleau, a hardliner from the right-wing Les Républicains party, claimed that the assailant had been under an "obligation to leave French territory" (OQTF) order, but Algeria had refused to accept his return.

Retailleau has repeatedly accused Algeria of undermining France, citing its reluctance to cooperate on deportations. His grievances were further fueled by a high-profile case involving 59-year-old social media influencer Boualem Naman, known as "Doualemn." Although legally residing in France for 36 years, Naman was deported to Algeria over allegations of inciting violence against an anti-government activist. However, Algerian authorities promptly sent him back to France, asserting his right to a fair trial in the country where he had long lived. A local court later lifted his deportation order, a decision that Retailleau vowed to challenge.

Cultural and political flashpoints

The diplomatic dispute has been exacerbated by the arrest of Algerian-born writer Boualem Sansal, a vocal critic of authoritarianism and Islamism. Sansal, who obtained French citizenship last year, was detained in Algeria on charges of "undermining the integrity of national territory" after an interview in which he suggested that parts of western Algeria rightfully belonged to Morocco.

This incident followed French President Emmanuel Macron’s controversial shift in policy, where he endorsed Morocco’s sovereignty over the disputed Western Sahara—an issue long contested by Algeria, which supports the region’s independence movement. Culture Minister Rachida Dati’s recent visit to Western Sahara further inflamed Algerian sentiments.

Yahia Zoubir, a senior fellow at the Middle East Council on Global Affairs, described the current crisis as unprecedented. “I’ve never seen it this bad,” he remarked, highlighting incendiary remarks from French political figures, including Nicolas Sarkozy’s son, who suggested burning Algerian consulates.

The political chessboard in France

Khadija Mohsen-Finan, a North Africa specialist at Paris Sorbonne-CNRS, linked the diplomatic row to France’s internal political struggles. The dissolution of the National Assembly in 2024 left no party with a clear majority, leading Macron’s allies to collaborate with the increasingly anti-immigration Les Républicains.

She argued that certain factions within the right-wing opposition have strategically positioned Algeria as a political adversary ahead of the 2027 presidential elections. “They’ve created an enemy that encapsulates the fears of immigration and insecurity,” she said, noting that this framing ignores the deep historical ties between France and Algeria, which was once part of France itself.

While Algeria is not the only country resistant to deportations, France’s statistics reveal a discrepancy: in 2024, only 42% of France’s deportation requests to Algeria were granted, compared to an average approval rate of 60% from other nations.

Colonial legacy and collective memory

Despite economic interdependence—France remains a key consumer of Algeria’s natural gas—the scars of colonial rule continue to shape bilateral relations. The legacy of French colonization and the brutal Algerian War of Independence still loom large in Algerian national consciousness.

“Memory is at the heart of this issue,” Zoubir explained. He noted that many Algerians believe France never fully accepted Algeria’s sovereignty, a sentiment fueled by Macron’s past comments downplaying Algeria’s historical identity before French colonization. Such rhetoric, he argued, only deepens resentment.

The discourse on colonial history remains highly charged in France as well. Far-right politician Marine Le Pen has controversially claimed that French rule in Algeria was not a “drama” for the local population. Meanwhile, journalist Jean-Michel Aphatie is under investigation for comparing French wartime atrocities in Algeria to Nazi crimes in occupied France—an analogy that has sparked heated debate.

Mohsen-Finan pointed out that the contrasting perspectives on colonial history continue to drive misunderstandings. “In France, there’s a silence on the war and colonization. Meanwhile, Algerians feel the French have conveniently forgotten 132 years of occupation and struggle,” she said.

An uncertain path forward

As diplomatic tensions mount, many fear the consequences for Algerians living in France—both legally and illegally. Mohsen-Finan warned that the growing criminalization of undocumented Algerians risks stigmatizing the entire community. “There are many Algerians in France—most of them legally residing,” she said. “But now, an entire country is being framed as the enemy.”

With neither side showing signs of de-escalation, the fracture in Franco-Algerian relations threatens to deepen, carrying implications far beyond migration policies. Photo by Mangostar, Wikimedia commons.